|

Breaking The Hindenburg Line In World War I

by New York National Guard Eric Durr

December 17, 2018

On September 29, 1918, the New York National Guard Soldiers of

the Army’s 27th Infantry division fought their way into the

defensive works known as the Hindenburg Line ... The attack did not

go smoothly and casualties were high.

At a cost of 3,076 men

wounded and killed over two days ... out of the division’s strength

of 18,055 ... the New Yorkers fought through a maze of German

machine gun nests and fortified positions and captured the leading

edge of the main German defenses.

One unit, the 107th

Infantry Regiment, famous as the 7th Regiment of the New York

National Guard, lost 396 men killed and had 753 men wounded out of a

total of 1,662 Soldiers who began the battle.

|

New York National Guard Soldiers

of the 27th Division's 107th Regiment training for the

planned attack on the Hindenburg Line during September 1918.

In this photograph the Soldiers practice moving through

barbed wire obstacles. When the actual attack kicked off on

September 29, 1918 the 107th Infantry lost 1,000 Soldiers

wounded and killed out of 1,662. (Courtesy New York State

Military Museum)

|

The costly attack, though, broke open the main German defense in

northern France and opened the way for the British Army to go on the

offense.

By the end of September 1918, most American Soldiers

in France were part of the First American Army Commanded by General

John J. Pershing. But the New York National Guard’s 27th Division

and the 30th Division, made up of National Guard Soldiers from

several southern states, had been “loaned” to the British Army and

fought under British command as the II Corps.

They’d fought

their first battle at the end of August 1918 and then pulled out of

the line to begin training for this major assault.

The

Americans were new to combat in the Great War, but they had one

thing the British—and the Canadians and Australians that fought with

the British Army did not have – numbers.

American divisions

were twice the size of British Army Divisions, and British Field

Marshall Douglas Haig knew he needed numbers for this assault.

For this battle the Americans were placed under the command of

Australian General John Monash, considered to be one of the best

commanders of the war.

Like the Americans he commanded,

Monash was a part-time soldier. He was an engineer in civilian life

but was an officer in the Australian militia.

When he went to

war he learned fast. He was successful without spending the lives of

his Soldiers.

The plan Monash came up with called for the

27th and 30th Divisions to lead the attack. Their large divisions

would make up for the fact that two of his Australian divisions were

effectively out of the fight.

The Americans would take the

St. Quentin Canal and then two Australian divisions would follow up

and leap frog through the Americans to finish the assault. The St.

Quentin Canal had been built in the early 19th century by Napoleon

Bonaparte when he ruled France. It was like a super-large trench.

A key feature facing the Americans was a 3.52 mile long tunnel

through a mountain. Inside the tunnel the Germans were using old

barges as barracks. It was like a huge bunker. They could wait out

the artillery and then pour out to counter attack.

At the

beginning of August the Americans were pulled out of the line and

began training for the fight. They learned to work with British

tanks. The tanks were critical because they were supposed to provide

fire power for the advancing Americans.

Monash sent 200

Australian officers to work with the Americans and make sure they

understood how he would fight the battle.

It could have made

for hurt feelings, but the Americans and Australians got along. They

both thought the British officers were a bit snobbish and they liked

each other.

The plan called for the Americans to launch a

preliminary attack and move up to a set line on September 27. This

“start line” for the main attack was what drove the plan for

artillery barrage—a wall of fire—which would cover the Americans on

their attack.

But things did not go as planned.

The

British division to the north of the 27th Division did not advance

as far as it should have during the preliminary attack. The

Americans of the 106th Infantry Regiment, which led the attack,

started further behind than they were supposed to and did not reach

the planned start line for the September29 attack.

Casualties

were heavy. In one battalion every officer was killed. They held the

ground where they stopped.

This meant American Soldiers were

holding the line in locations where allied artillery should be

falling to allow the 107th Infantry Regiment to attack. In World War

I communications were so slow that artillery fire had to be planned

well in advance. There was no easy way to adjust fire.

So on

the morning of September 29, the Americans would have to move more

than a half mile in the open before they caught up with the

artillery barrage.

At 5.55 a.m. on September 29, the attack

began. The 107th Infantry Regiment attacked on the left of the 27th

Division front while the 108th Infantry Regiment attacked on the

right. Artillery fire fell on the Germans but not the Germans right

in front of the Guardsmen. They kept attacking but they took heavy

loses.

The tanks that were supposed to provide fire support

got knocked out by artillery fire and in some cases old British

mines. The Soldiers were pinned down by German machine gun fire and

counterattacks.

|

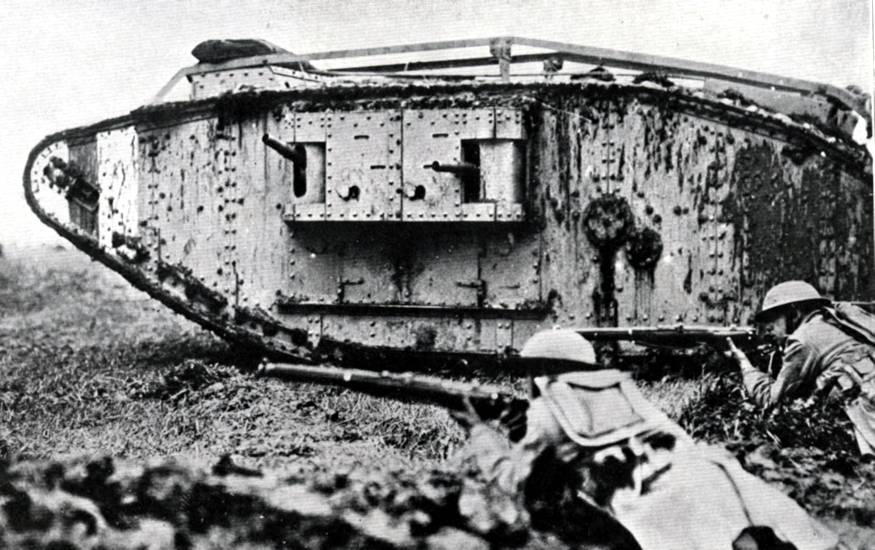

Soldiers of the New York National

Guard's 107th Infantry Regiment, a part of the 27th

Division, train with a British machine-gun armed tank during

training for the assault on the Hindenburg Line during

September 1918. When the attack kicked off the 107th lost

1,000 men wounded and killed out of a strength of 1,662. The

tanks that supported the attack on September 29, 1918 were

quickly knocked out. (New York National Guard Courtesy

Photo)

|

The 107th Regiment continued to attack but took very heavy loses.

“They were more than seasoned veterans,” Major General John

O'Bryan, the commander of the 27th Division wrote after the war,

“for in addition to battle experience and technical training they

possessed in fullest measure pride of organization, high sense of

honor and a strong sense of accountability to the home land and the

family.”

“The roster of the dead contains the best names of

the city of New York—best in the sense of family tradition and all

that stands for good citizenship in the history of the city. This

comment applies as well to the rest of the remainder of the regiment

and in the same way to the remaining units of the division, which

represented other cities and localities of New York State, “he

wrote.

The well-tuned plan fell apart and the Soldiers fought

in small units and companies. The fighting was often hand-to-hand,

which surprised the Germans. By the afternoon of the 29th some of

the 27th Division units had reached the St. Quentin tunnel. But

others were still pinned down.

General Monash blamed the

Americans for not sticking to his plan. The Americans, Monash told

an Australian war reporter “sold us a pup … They’re simply

unspeakable”.

The confusion on the ground made it impossible

for the Australians following the 27th Division to “leap frog”

through the Americans and Monash directed the Australian units south

of the St. Quentin Tunnel where the 30th Division had better

success.

In other cases Australians joined members of the

27th Division in the attack.

Historians, though, say Monash

was unfair to the men of the 27th Division. Because they were not

able to start the attack where they should have, their lines were

thin and they had to advance further than they should have.

The fighting continued on September 30 and the Germans began to give

away. By October 1, 1918 the Americans and Australians had cleared

out the fortifications.

|

New York National Guard Soldiers

of the 108th Infantry Regiment of the 27th Division cross a

bridge over the LeSelle River on their way to St. Souplet,

France during the Hindenburg Line campaign in the fall of

1918. The bridge was built by the Soldiers of the 102nd

Engineer Battalion. (Courtesy New York State Military

Museum)

|

After the war, and outside of the heat of the battle, Monash was

generous to the men of the 27th Division.

“I have no

hesitation in saying that they fought most bravely, and advanced to

the assault most fearlessly, “he wrote.

“The leaders, from

the Divisional Generals downwards, did the utmost within their

powers to ensure success. Nor must the very bad conditions under

which the 27th Division had to start be forgotten. Our American

Allies are, all things considered, are entitled to high credit for a

fine effort,” Monash wrote.

During the World War I centennial

observance the Division of Military and Naval Affairs will issue

press releases noting key dates which impacted New Yorkers based on

information provided by the New York State Military Museum in

Saratoga Springs, N.Y. More than 400,000 New Yorkers served in the

military during World War I, more than any other state.

|

|